There is an immense interest in sports like hockey, boxing, wrestling, javelin, badminton, shooting, and weightlifting whenever there is a multi-sport event. Take the Paris Olympics 2024 as an example. The way India collectively cheered for the contingent was heartening to see. But sadly, the same enthusiasm fizzles out completely as soon as the event ends. So much so that there is almost negligible interest in what the athletes are doing in between.

The same, however, is not the case with cricket and its stars. India doesn’t need a World Cup or a WTC final to show interest in its cricketers. The fandom is throughout the year. Yes, it definitely rises during ICC tournaments or a big series but it never nosedives like other sports.

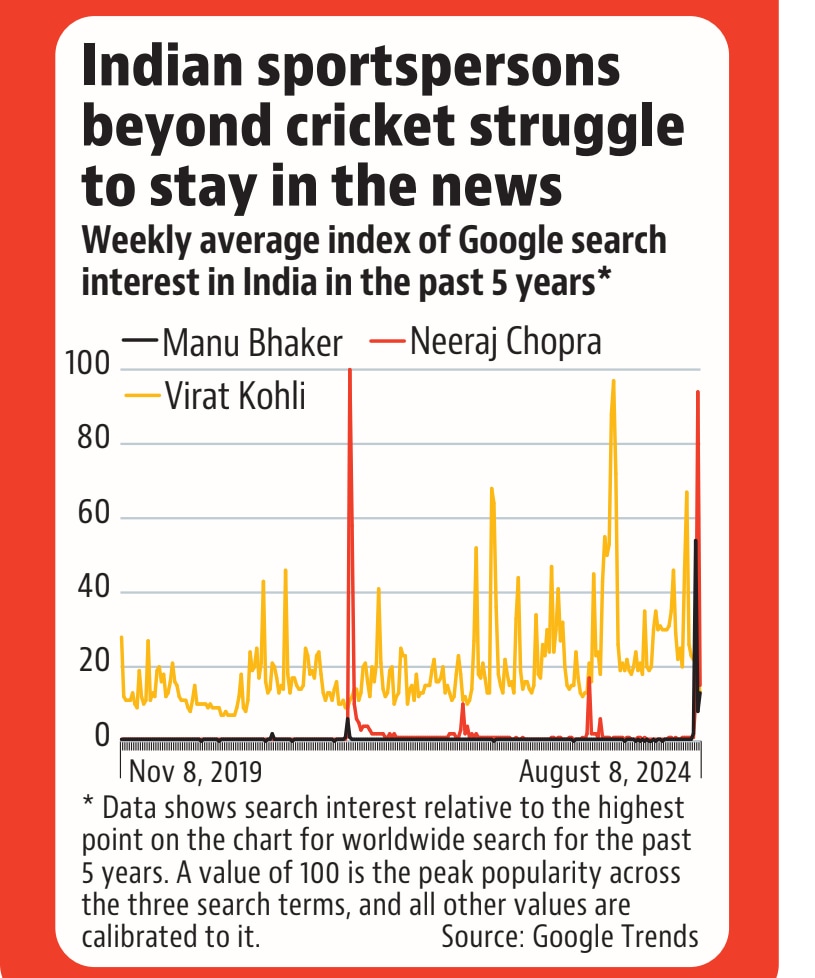

HT compared Google search interest over the last five years for three of India’s top sportspersons: cricketer Virat Kohli, shooter Manu Bhaker, and javelin thrower Neeraj Chopra. This data offers four lessons – Kohli always occupies fan mind space. For non-cricketers in India, it takes an extraordinary achievement to occupy that space. During this period, the highest interest was for Neeraj Chopra when he won gold at the Tokyo Olympics in 2021. For Bhaker and Chopra, there is barely any interest barring the Olympics, Asian Games and Commonwealth Games. They don’t compete in India with crowds and prize money. In other words, their sports need more support and handholding to develop and expand the pipeline of those coming through.

There can be various reasons behind this. However, the most apparent ones are the lack of targeted publicity, broadcasting, investment, advertising, and awareness. It’s not like there are no shooting events apart from the Commonwealth Games, Asian Games or the Olympics. There are plenty. But how many of them are broadcast? Even if they are, how many know about it? This is just one aspect of the story.

The kind of attention Manu Bhaker or Aman Sehrawat has got in the last month won’t be replicated until the next big multi-sport event; perhaps they also know this. And this indirectly plays a part in India’s overall development as a sporting nation.

India was expected to deliver its best-ever Olympics medals haul in Paris 2024. It ended with six medals, one less than its best ever showing at Tokyo 2020. In Paris, India also had six fourth-place finishes, and a disqualification that turned a medal into a no-show, leading to narratives of what might have been. What will it take to deliver more Olympic medals? The answer is a lot, at many levels. From deepening and widening of the playing of sports at the grassroots level, to strengthening the transition to playing at competitive levels, to sharpening the support for pursuit of medals at the very top.

Targeted funding

India’s quest for more Olympic medals has been centered at the top, via the Target Olympic Podium Scheme (TOPS). This central government-funded scheme identifies medal prospects and extends financial support for their training and competition during the Games cycle. Some sports have benefitted. Take shooting. Under TOPS, in the Paris Olympics cycle, the government reportedly spent ₹60 crore to support 28 shooters. In Tokyo 2020, India’s 20 participations returned an average placing of 19. In Paris, the 28 participations averaged a placing of 13, including 3 medals. The targeting of elite athletes was a key lever Great Britain pulled to reclaim its status as a leading Olympic nation. After winning just 15 medals at Atlanta 1996, it set up UK Sport in 1997. Funded by the National Lottery and the government, it invests money in Olympic and Paralympic sports, aimed at building a high-performance culture with an implicit pathway to Olympic medals.

Funding scale

In 1996 Britain’s 15 medals came from 6 sports. In 2024, its 65 medals came from 18 sports. Six sports yielded more than 5 medals: cycling, athletics, rowing, diving, equestrian and swimming. While UK Sport backs 33 sports, 49% of its funding since May 1997 has gone to these six sports. UK Sport funds at two levels: to a sporting programme and to individual athletes. UK Sport data for the Paris 2024 cycle is not available. But in the Tokyo 2020 cycle, it ploughed 338 million pounds towards Olympics and Paralympics. At the then rupee-pound exchange rate, that’s roughly ₹3,000 crore, for a squad about three times the size of India’s. In the Paris cycle, India spent about ₹470 crore, including funding under TOPS and from corporates. Elite sports is expensive.

System change

Any successful sport reolves around a self-perpetuating cycle of widespread adoption, globally competitive events, commercial outlets, fan interest and on-field success. In India, cricket has created that cycle. Badminton has made strides in the past two decades. Beyond them, most sports are struggling to craft that foundational circle. The sports bodies tasked with that are often corrupt or are plagued by deficits in finances, governance, and imagination. Sports Authority of India has registered an average income increase of just 9% between 2014-15 and 2021-22, the latest period for which its data is available. For the ministry of sports, SAI’s biggest funder, that increase is 10.5%. Federations remain weak and are bastions of politicians. While they receive government funding, in the context of promoting the sport at the grassroots, holding competitive events and nurturing talent, their budgets are puny.